Within weeks of selling Wolfish, I became fixated on my insecurities, tugging at them like hangnails. Surely I was not well-organized enough, not dogged or savvy enough, to write the book I now had to write. My anxiety was essentially narcissistic. I was drunk on a story I had invented about how I would be perceived. My biggest fear was that I—a person who had never seen a wolf in the wild, who had once accidentally cried in front of a science professor because I was scared for the exam—disqualified me from writing anything good about wolves.

This was late 2020, and some dark night during that first pandemic winter, I realized the only thing harder than having to write this book would be admitting I needed to give back the money because I couldn’t do it. I needed to reframe my mindset, fast. I began to stumble my way through a new story: What if the thing I thought made me the wrong writer of this book was actually the thing that made me the right one? I wasn’t a trained scientist, I was, as I later wrote “just one animal watching another,” a curious amateur, someone who clocked the wolf t-shirts worn by members of bachelor parties, as interested in wolves wandering pop songs as prairies. Maybe my roaming omnivorousness was not dilettante-ism; it was the point.

Last month, while teaching a researched memoir workshop for

, I asked attendees to perform a similar mental gymnastics, reframing their so-called achilles heel into their so-called superpower. Days later, during a meta-relationship-check-in (we stan the Gottman State of the Union framework, it feels corny but it just works), Sam kindly reminded me that this was true in life too: the parts of my selfhood I struggle with most are intermeshed with the parts I hold most beloved. When I told him I had 38 unread text messages and was in a state of self-hating overwhelm about being a shit communicator, for example, he reminded me that actually I was a good communicator, I just texted tens of people every day from different corners of life and work. This—combined with trying not to be on my phone very much so I could prioritize writing, wellbeing, and in-person socialization—meant I often responded slowly to non-urgent matters. Which was (sorry) actually nbd. The parts of self that make me feel like a bad friend are directly tied to the parts that make me a good one.Re-framing the relationship between inner strengths and challenges soon opened an entirely new door for self-reflection: It gave me an excuse to own up to that which I’m (happily) mediocre at. This is nothing to mourn. As my genius friend Linda Kinstler once told me, Don’t stress about spreadsheets if you don’t care about being good at spreadsheets. In her book Saving Time, Jenny Odell challenges ambition-wired perfectionists to “Experimen[t] with what looks like mediocrity in some parts of your life. Then…have a moment to wonder why and to whom it seems mediocre.” Not only does one not have to be “good” at spreadsheets, one should ask why the expectation of excellence exists at all.

As a recovering child perfectionist, I have started keeping a running brain-list of all the things I relish being so-so at. For example—gardening. Sure I want to grow some nice blooms and apocalypse kale, but I am also fine with the presence of weeds and patchy grass and imperfect irrigation. I also recognize I am never going to master putting on eyeshadow, cool gym outfits, or a dust-free living room. My house plants will always be a little over-or-under-watered. I’m a slacker in the group chat (but I love being there!). I don’t know TV shows or meme references until they’re old news. In the last six months I started re-playing violin after 15 years away, and you know what, I squeak. Inventorying everything I don’t mind being mediocre at has helped me distinguish what I really want to prioritize, though: connecting with a wide range of people, feeling strong in my body, reading and writing voraciously.

The main reason I haven’t written here in so long is that, earlier this year, I sold my second book. It’s about love amidst catastrophe, and how disasters push us together and pull us apart, and it thinks deeply about the interplay between romance and community, and how we might imagine a future where we can better love in both. (It’s the biggest honor to be working with Flatiron again—with a new editor, the brilliant Lee Oglesby—and with Faber in the U.K, where Hannah Knowles, the acquiring editor for Wolfish in the U.K., is now based.) To write a book, you have to know what you’re going to let slide. The group of writers I co-work with every week sometimes do an exercise where we go around and say three things we’re not going to focus on in the month to come. Celebrate the mediocrity that will come: it is evidence of energy tunneled elsewhere.

Jenny Odell’s definition of mediocrity—a value judgment perpetuated by normative capitalist Western culture—reminds me of a line that stuck out to me from

’ Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change. “What if every child believed that being ‘good’ at a sport or activity…means that you enjoy doing it?” writes Garbes. In this framework, I get “good” at gardening when I feel a sense of growth and fulfillment in the dirt, not when I achieve an Instagram-worthy yard. It’s felt liberating to re-frame what it means to be both “mediocre” and “good.”Culturally, we are really fucked around our language around ambition. To frame it in terms of personal growth—and thus to celebrate, as so many have since the COVID pandemic, a de-escalation of ambition in an era of ‘quiet-quitting’ etc.—is to neglect how desperately we need to cultivate ambition for our collective future. Independent ambition = desire to propel one’s own literary career. Collective ambition = desire for a literary landscape where provocative and lyrical books find new readers despite an increasingly AI-algorithm-ed hellscape. Sure, I want to get paid dollars-a-word for magazine essays, but really that means I want a public that values art and writing.

My thinking on large-scale ambition has stemmed from book research I’m doing on visions of the future. Early utopian writers depicted paradise as a remote place waiting to be ‘discovered’—the colonial fantasies of a hidden Shangri-la—but by the end of the 18th century, the vision had changed from “an undiscovered somewhere to a forthcoming somewhen…a paradise that we would build for ourselves,” as Chris Jennings writes in Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism. To get there—to dream there—we need a lot of collective longing, hunger, and action.

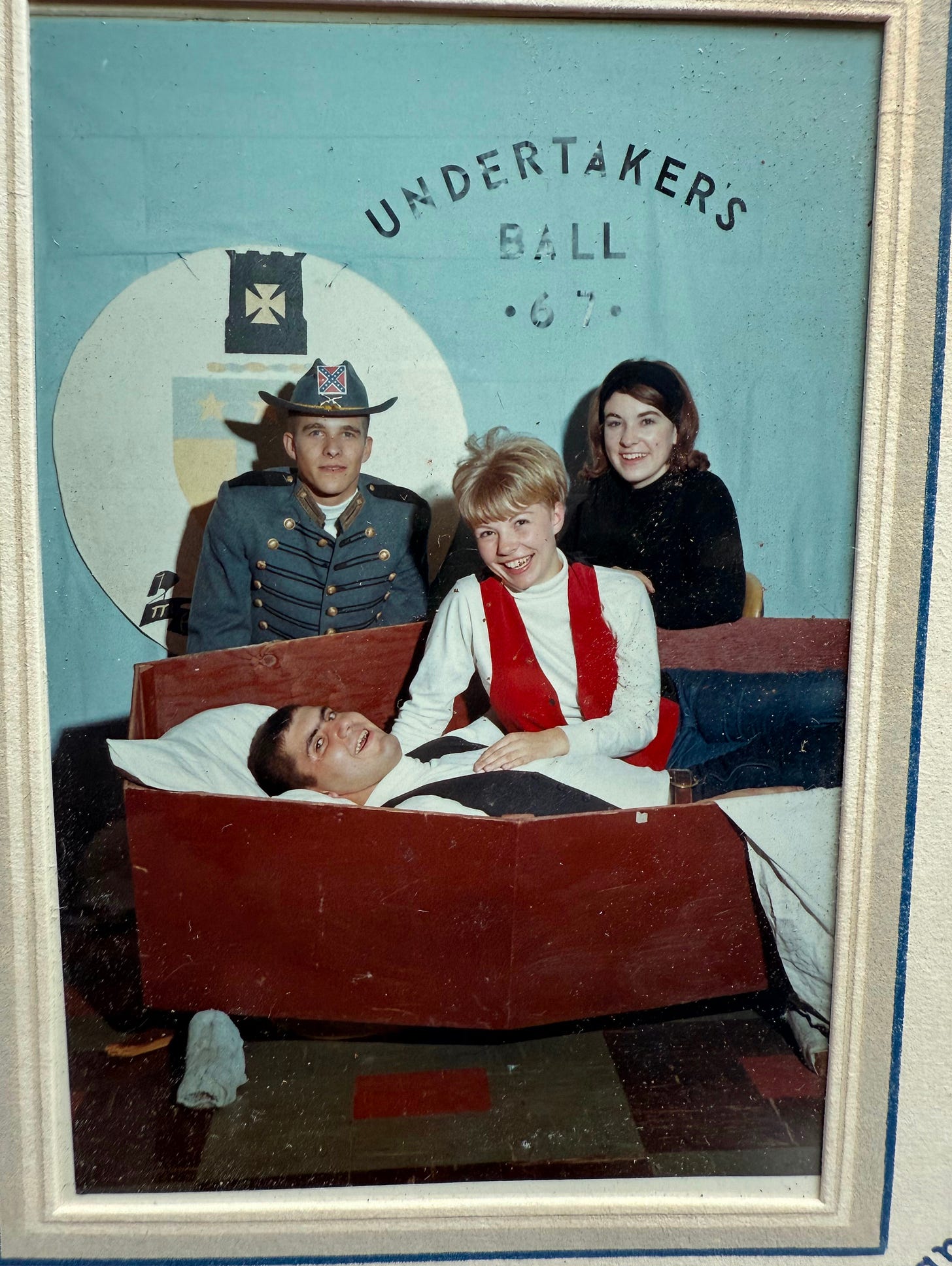

When I played violin in middle school, I wanted to excel. Back then I thought I might get into college based on some musical precociousness (related: this

essay), or at least impress a boy at Saturday symphony. Now I want only to feel the gut-twirl that comes with creating sound where, a minute earlier, there was silence. If I’m lucky, I’ll play music with friends in somebody’s living room. We’ll sound okay, and I’ll love that for us. I’m not practicing because I want to be exceptional. I’m practicing because it reminds me we are fighting for a world where more people will have time, space, and energy to gather together and squeak through songs.What else?

I always forget that every season is busy except mid-winter. February is the only chill month and every other is bonkers. This spring I got a teary-eyed thrill when I received a 2025 Career Achievement Award from Literary Arts, the Portland-based nonprofit that generously supports writers and writing throughout the state of Oregon, and beyond. Mostly I’m in book-research mode, excited to share tidbits with you soon.

“Why do we welcome some animals and plants into our lives, while we reject others?” This podcast, recorded last spring in Pendleton, Oregon, highlights one of my favorite post-Wolfish conversations. Support Oregon Humanities!

Way back when, Unherd asked me to write about an old book that was relevant today, so naturally I wrote about Parallel Lives, Victorian marriage, and heteropessimism.

For Emergence’s “Time” issue, I wrote about living with uncertainty, in our bodies and the land.

For Orion’s awe-inspiring mushroom issue (

! Lydia Yuknavich! !!) I wrote about lurking in Facebook groups, and the poison, pleasure, and terror of both foraging and falling in love.On the calendar:

My friend and fellow writer

and I are holding our second fundraising “Write-a-thon” on June 29, where a bunch of Portland writers will get together to pledge money, then write in silence with a beer for two hours. If this is your kind of Sunday afternoon, join us!I’m reading at Lewis and Clark College during the Fir Acres Writing Workshop on the evening of June 30.

Very excited to visit River Arts Books in Roscoe, Montana, for a reading on the evening of July 31.

I leave you with a throwback windows-down driving album, a perfect veg pasta recipe, an old friend’s incredible book to pre-order, and a place to send in all your weird-colored clothing to be beautifully re-dyed.

More soon, I promise.

xxE.

Erica, I treasured this as much as I treasured Wolfish. Embracing our mediocrity at certain tasks is so liberating - I’m so grateful for this perspective. As a wannabe-writer, I get so much out of your presence in my inbox. Thank you for sharing what you do!!!

This is wonderful.