A few nights ago I dreamt I was escaping a big wave; a night later, that I was escaping a big fire. I’m spending the month at an artist residency on the Long Beach Peninsula in southern Washington, a coastal spit so skinny and flat that ‘vertical evacuation routes’ such as towers are recommended to survive tsunamis. I have no tower, I have a one-room cabin tucked beneath the trees. Though I jog most days, a loop between the oyster mudflats on the peninsula’s bayside and the frothing Pacific on the other, the view from my desk is all leaves and pine needles. The lack of waterfront-adjacency feels like a strange blessing. It is easier to ignore my go-bag—a red backpack the residency pre-loaded with emergency supplies that sits on a shelf above the coffee pot—when I can forget about why I might need it.

The wildfire smoke complicates things. It stymies my efforts at denying catastrophe. This week, the Pacific Northwest has the worst air quality in the world. When the smoke came last week, I pretended it wasn’t here, but then the headache came, so I dutifully went inside, shut the windows, Googled where was burning. A few towns across the river from Portland were being evacuated, a place I had recently driven through en route to a hike. Fuck, fuck, fuck I thought, and then, because I didn’t know what to do with all my fucks, I ate some Chex Mix, I answered an email.

Mid-October here has never, in my memory, felt like this. My birthday on the 11th always seemed like an unofficial divider: my past and my future, the summer and the fall. This year the birthday has come and gone, and I am still eating peaches on my porch step, the leaves around me shaggy and green. I felt gutted when the fires came for Oregon summer (I wrote about it for The Guardian in 2020), but it feels particularly rude that they have now come for fall, my birthday season. The footprint of the wildfires no longer feels just spatial (land that has burned) but temporal (weeks now filled in smoke). To be affected by smoke and not flame is, of course, to be one of the fortunate ones. But just as life here means living in anticipation of “The Big One” (not if but when the earth will shake), so too does it feel like a wait for fire. Continued suppression only makes these fires harder to contain.

I keep thinking about what October means—what it conjures, as a seasonal construct—when the smoky days smell like grief, rage, fear. Being in air like this feels like trying to eat while a dog whines at the foot of the chair: heed me, heed me, heed me. I can only look away for so long. Part of why I resent this autumn is that turns me into a bitch. I don’t want to see your cozy Vermont barn wedding! I think, scrolling Instagram. How dare you flaunt a pumpkin on an orange leaf-strewn stoop. Today I walked by a pumpkin sitting alone beneath a row of green trees, and it looked so dumb I almost kicked it. Where do you think this is, LA? As if it were the pumpkin’s fault for being the only orange thing on the whole block. My resentfulness, of course, comes from a strange loneliness: that my friends in other places do not understand the hollow sadness of this month out west.

The season feels so uncanny that my mind has started to assume responsibility. You’re in a dream, I think, burrowing my toes in warm sand while I watch two fisherman wade into the Pacific a few weeks before Halloween. In this dream, Washington has just merged with Southern California. The dream fades when I see an email about record-breaking highs and an air-quality alert, and another, from a local Portland cafe, noting that because it is 80 degrees they are still stocking 'chillable reds.' Though thinking about these days gives me floaty nausea, living them—and this must be said—sometimes feels pretty good. When the wind changes, blowing the smoke into another town, I can sit on the beach in my t-shirt, stoned on Vitamin D. What I mean is that the dissonance of grief and pleasure is astounding. How does one bask in the sun of another’s drought? How does one face these days if we deny ourselves the basking?

I just finished reading the climate activist Daniel Sherrell's Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of the World, a lyrical meditation on what it means to be alive and attuned right now, written in the form of a letter to his unborn, hypothetical child. "I am not asking here whether I should have you," he writes toward the beginning, "but what I owe you if I do." I found this framing refreshing. Too often my gut instinct is to experience the daily toll of global warming as a parade of gross choices stalked by guilt: should I take the plane ride, should I buy the salad in the plastic box, should I take a pleasure roadtrip in a gas-fueled car. In this way, my conceptualization of what it "feels like" to be alive right now becomes inordinately about self-loathing, about individual choice in the consumer sphere. The concept of a 'carbon footprint', of course, was popularized by BP oil to privilege individual responsibility over collective action. I do think it's important to conserve resources in our individual lives—I'll never stop trying to reuse aluminum foil, or walk short distances instead of drive—but I do it almost as an act of mindfulness, not because I think I’m saving the world, but because it feels essential to continually acknowledge the webs of labor, capital, and resources that prop my body up.

Reading Sherrell, though, I understood how sick I am of discourse that considers 'Should I have a child?' and 'Should I eat this fish?' through the same moral lens. Both questions become essentially about the ethical duty of the individual as consumer or producer. I am tired of summing myself as inputs and outputs. Too often I frame my waffling and decision-making paralysis through the lens of my being a Libra, but pop astrology becomes my scapegoat. It becomes easier to chuckle at my hardwired indecision than to examine the cultural systems that have created impossible choices. (I'm thinking about sociologist Eva Illouz on the "generalized 'uncertainty'" that defines modern relations, which, she clarifies, "does not point to the universality of a conflicted unconscious but rather to the globalization of the conditions of life").

Maybe I am compelled by Sherrell's thesis (which asks not 'whether' but 'how to be' if I do) because it precipitates a future. It incites imagination, rather than stoking the belief that the livability of a future planet depends on one's right or wrong choice in the now. "A failure of imagination means a failure of the spectrum of futures that are available to us," marine biologist and climate-solutions thinker Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson said on Krista Tippett's podcast, On Being. Johnson explains that rather than being guided by hope, she is compelled by "the amount of possibility that's available." That’s the word—possibility—that she thinks of when she imagines, 'What if we get this right?’ What if we have the tools to flight climate change right now?

I write this slumped in an armchair. I jogged today, because I knew it would make me feel in control, but I underestimated how the smoke—equivalent to inhaling a few cigarettes—would bring a hangover. My head is cloudy. My throat prickles. And yet: We have just lived through what might be the coolest summer of the rest of our lives, and still—still!—there is possibility in whatever weird seasons lie ahead. Gradations of heat, gradations of support and care. Wildfire smoke is exacerbating care deserts throughout the American west, highlighting a need not only for more pulmonologists, but better rural health care, better ways to pay for it. Yes, smoky October sucks, but it is not the apocalypse: there is so much more that can be done.

I hold that word, possibility, like a lozenge on my tongue. I feel it’s drip. I turn to the too-green trees, I face the too-hot sun.

Welcome to this mailing list, or newsletter, or little shard of your inbox.

I wanted to write about solitude and socializing, and then I couldn’t stop thinking about smoke, oops. I envision sending about two posts a month, both to send updates about my forthcoming book, and because I like the challenge of unspooling my brain in short, low-stakes essay rather than little pellets on social media.

I am calling this ‘Away Message’ because I liked writing ‘Away Messages’ whenever I went offline on AIM…like leaving your coat on the chair at a party, a good Away Message can create a space, a pause, a provocation. An Away Message is not seen by everybody all at once, it doesn’t have to be responded to, it doesn’t need to seed a conversation. That said, I’d always love to hear from you.

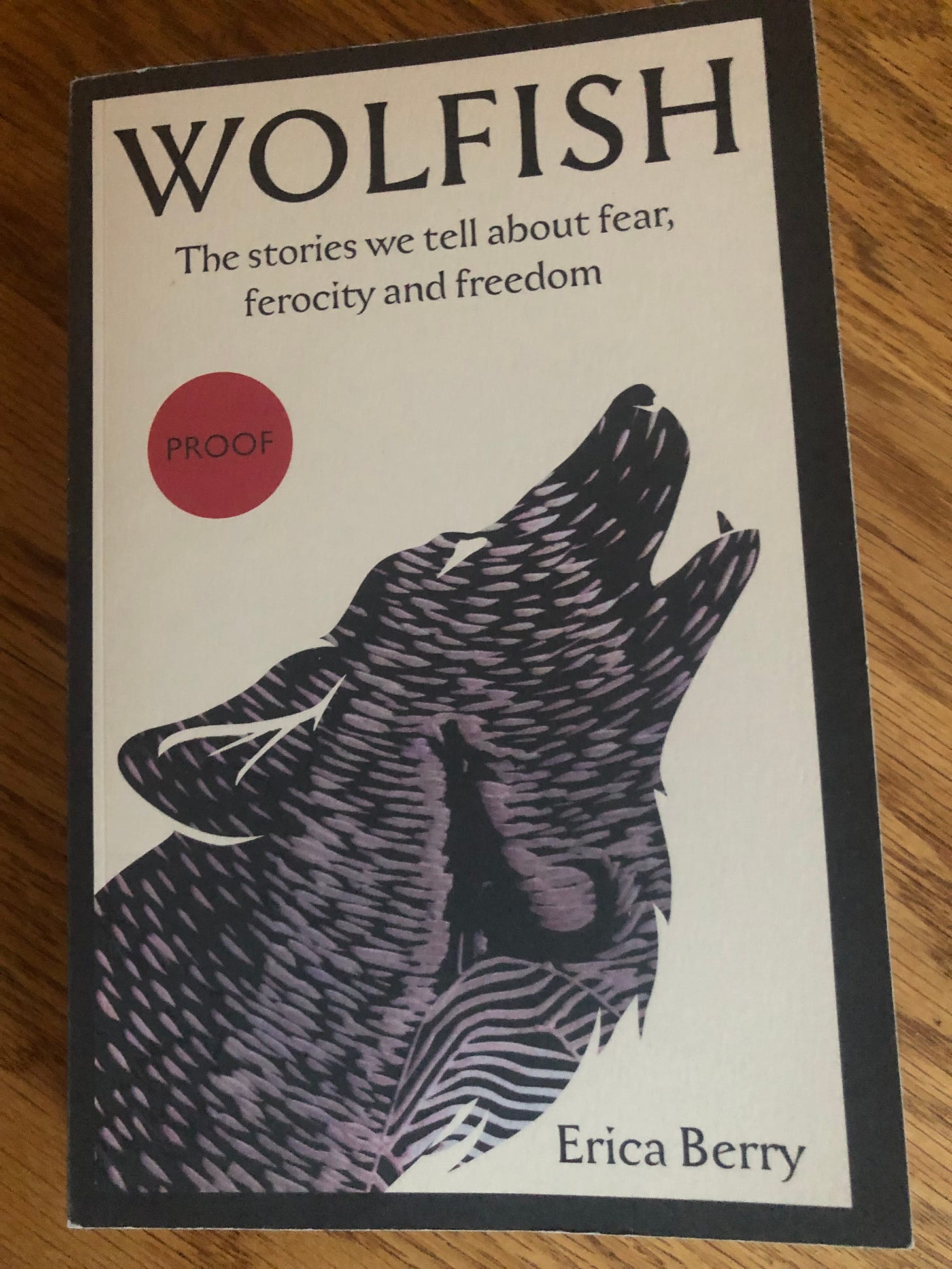

ICYMI, my first book, Wolfish, will be in U.S. bookstores on February 21, and in the U.K. on March 2.

It’s a book that is interested in both real and symbolic wolves, and about the the feelings that we so often project on them: fear and grief, love and loss. It’s about what our gaze on the natural world can tell us about ourselves. Some of my favorite writers have said some really, really nice things about it. Journalist and author Lyz Lenz called it "a triumph of a debut, cementing Berry as an important new voice," and Pulitzer-finalist Elizabeth Rush said she “devoured every startling, lyrical, haunting page" and it "left [her] feeling like one of the pack.”

If you want to support this book:

You can preorder a signed and personalized copy from my local indie bookstore and they will ship it to your door <3

I am told it is very helpful if people 'add' the book to their Goodreads, and, eventually, review it there. I am also told I should never read these reviews : /

I just learned you can ask your local bookstore/library to stock any book. Many libraries have easy-to-fill-out request forms on their websites, but you need a local library card to do this. I am grateful if you do this!

I am beginning to book some 2023 (and 2024!) readings and talks with colleges, nonprofits, and bookstores. Do you have an idea of a place you think this book and I should visit? or a group you think I should reach out to? Get in touch.